A University English Grammar R Quirk S Greenbaum Longmans Pdf

000a 000b 000c 000d 001 005 009 013 017 021 025 029 033 037 041 045 049 053 057 061 065 069 073 077 081 085 089 093 097 001 105 109 113 117 121 125 129 133 137 141 145 149 153 157 161 165 169 173 177 181 185 189 193 197 101 205 209 213 217 221 225 229 233 237 241 245 249 253 257 261 265 269 273 277 281 285 289 293 297 201 305 309 313 317 321 325 329 333 337 341 345 349 353 357 361 365 369 373 377 381 385 389 393 397 301 405 409 413 417 421 425 429 433 437 441 445 449 453 457 461 465 469 473 477 481 400.

This chapter is based on an interview with Keith Brown in February 2001 Like everyone else, I suppose, I'm very much a product of my background and childhood, the child being father of the man, as Wordsworth said. I was brought up in a farming family to be obsessively enamoured of hard work and to be just as obsessively sceptical about orthodoxies, religious or political. So in retrospect it's easy for me to see why I became such a restless, free-ranging eclectic as I have been. You see, my family was a mixture of catholic and protestant, of anglican and methodist, in an island community where self-consciously Manx values cohabited uneasily with increasingly dominant English values.

Indeed, if I'm an eclectic pluralist, it may simply be that the Manx in general are. Although we tend to be a bit equivocal and semi-detached about national identity, we're very conscious of our Celtic roots: we share St Patrick with Ireland and we have the remnants of a Celtic language that is close to being intercomprehensible with Irish.

I say 'remnants' because, although the rudiments are now taught in school, when I was a child there were already very few fully competent Manx speakers, and most of us (though living in Manx named Ballabrooie or Cronk y Voddy) only used Manx for the odd greeting or proverb or our very own euphemism for 'loo', tthai beg 'little house'. But we were conscious too of Scandinavian roots.

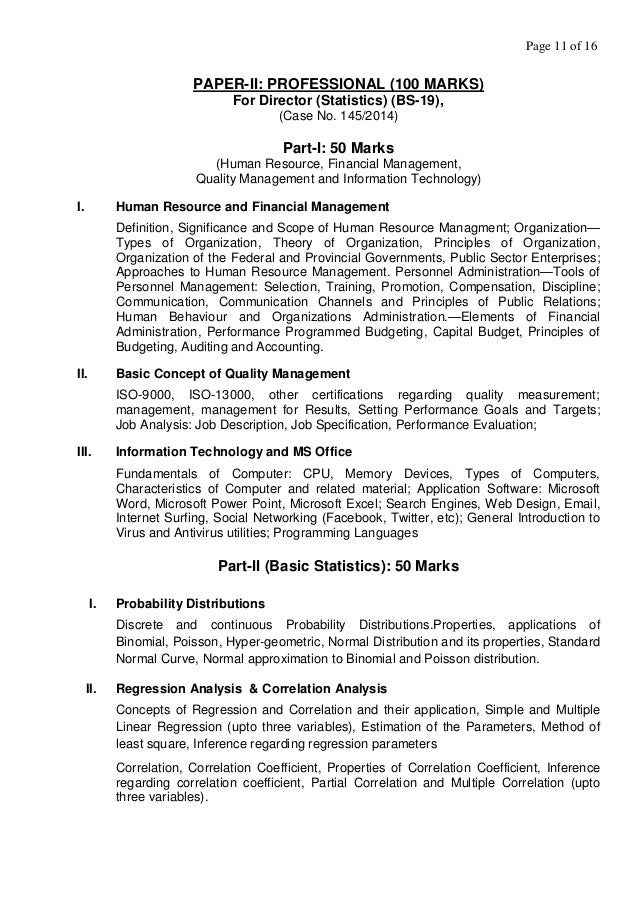

Based on 'A grammar of contemporary English', by R Quirk & others. A university grammar of english / Randolph Quirk, Sidney Greenbaum Quirk, Randolph.

We sang of King Orry and bowed to St Olave; we proudly gawped at our quite splendid Viking-Age crosses with their runic inscriptions - some of the best in Kirk Michael only a couple of miles from our family farm which itself bears a Scandinavian name, Lambfell. The Manx parliament has retained its Scandinavian name for a thousand years: Tynwald, cognate in form and function with Iceland's Thingvoll. In the middle ages, our bishop was appointed from Trondheim and his title still recalls that his domain once included 'Sodor', which derives from the Scandinavian name for the Hebrides. You may well be wondering, but are too courteous to ask: What has all this to do with my academic career? Well, in addition to underlining this nonconforming eclecticism of mine, it may help to explain my interest in language, history, and language history. So when I had reluctantly abandoned school science for the 'arts', I came to UCL, eventually settling for the subject 'English' because of the historical and linguistic bias in the curriculum: Gothic, some Old Saxon and Old High German, a lot of Old Norse, and even more Anglo-Saxon: Germanic philology, history of language and the writing of language: palaeography from runes to court hand. Not that the course of my true love for this English degree ran smoothly to begin with.

I diverted some of my energies into the lively politics of the time, and a lot into music - especially into playing in a dance band, not least to fund nights out with girls. The war had made my bit of UCL re-locate in Aberystwyth and I was further diverted into dabbling in the Welsh spoken around me, tickled that Cronk y Voddy's tthai beg was Aber's ty bach. I still love singing those minor-key Welsh hymns - in Welsh. But most seriously I was diverted from the English degree by five years in RAF's bomber command where I became so deeply interested in explosives that I started to do an external degree in chemistry through evening classes at what is now the University of Hull. But with demobilisation in 1945 I suddenly felt middle-aged and so I soberly resumed my UCL degree with unexpected dedication, enlivened by new excitements.

With the College back in Bloomsbury, I discovered I could tap into phonetics with Daniel Jones and (just down the road at SOAS) into a subject then just daring to speak its name ('linguistics') with J.R.Firth. By the time I'd got my BA, I was hooked on the idea of research. Ah, but in what?

It's hard now to explain to young graduates how lucky we were in austerity England, bombarded with tempting career offers. I was invited to take up a research fellowship in Cambridge to work on Old Norse (and in fact I did subsequently do some bits of work on Hrafnkelssaga and a student edition of Gunnlaugssaga with P.G.Foote in 1963). But I was counter-attracted by the offer ( offer: no ad, no application, no referees) of a junior lectureship at UCL itself. Without so much as an hour's teacher training, I happily charged into undergraduate classes on medieval literature, history of the language, OE, Old Norse, and anything else the powers thought I had more time to do than they. And then there was the exciting challenge of embarking on research - a matter far more important in the eyes of the said powers. At that time, there was much controversy over a now yawn-inducing issue in old Germanic philology: what Grimm had called Brechung.

Were the vowels in OE words like heard 'hard' or feoh 'cattle' really diphthongs or just simple vowels plus diacritics indicating consonant 'colour'? With great gusto, I took on Fernand Mosse of Paris and Marjorie Daunt of Birkbeck, with the enthusiastic approval of my supervisor, A.H.Smith. Supervision was often rather nominal in those days, and so it was with Hugh Smith, but it was always a privilege to have ready access to such an extraordinary polymath: big in toponymics, of course, but big also in ultra-violet photography, horology, and typography, to name just a few of his interests. My research involved learning some Old Irish where the vowel graphemics showed apparent similarities (and where the stories from the Tain held - like the Norse sagas - a literary interest for me as well). My work also involved learning some Danish and Swedish for a lot of the relevant published research. So it was that I came to sit at the feet of Elias Bredsdorff, the Hans Andersen scholar, then lektor in Danish at UCL, who could sometimes be coaxed into telling of his exploits in war-time Denmark when he was prominent on the SS wanted list. Despite such temptations to dawdle and dabble, the thesis got finished but (astonishingly as it may now seem) the controversy rumbled on, joined by up-and-coming Bob Stockwell on the one side and Sherman Kuhn stoutly joining forces with me on the other.

Here You Can Krishna Theme (Flute) - Himesh Reshammiya download in zip HD quality and listen all songs. Krishna Theme (Flute) - Himesh Reshammiya lyrics Target 40 - Krishna Theme (Flute) - Himesh Reshammiya video hd Krishna Theme (Flute) - Himesh Reshammiya mp3 download mp3 download Krishna Theme (Flute) - Himesh Reshammiya download Krishna Theme (Flute) - Himesh Reshammiya brand new punjabi song full hd Krishna Theme (Flute) - Himesh Reshammiya Krishna Theme (Flute) - Himesh Reshammiya is Available in Bollywood On DjPunjab.Com. Indian krishna flute music.

Meanwhile, teaching students OE was bringing home to me how little Germanic philology helped them and how much syntax and lexicology would. So for my PhD, I switched to syntax, incurring some displeasure among the powers for whom sticking to one's scholarly last was a prime virtue and my field was phonology, was it not? But in one quarter the switch was welcomed. A book based on my thesis was published by Yale University Press in 1954 ( The Concessive Relation in Old English Poetry) just whenC.L.Wrenn at Pembroke, Oxford was planning to write an OE grammar. Because such grammars traditionally covered only phonology and morphology, he roped me in to help write a different kind of text book, replete with a fairly full treatment of syntax as well as word-formation. An Old English Grammar was duly published by Methuen in 1955. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

A University English Grammar R Quirk S Greenbaum Longmans Pdf

Before that collaboration with Wrenn, I had another life-changing stroke of luck. In 1951, I was awarded what is now called a Harkness Fellowship that took me to Bernard Bloch, Helge Kokeritz, and Yale. I rejoiced in attending Bloch's classes as a 'post-doc' but revelled also in the proximity (given a splendid car and the Merritt Parkway) of Columbia and Cabell Greet to the south and of Brown (Freeman Twaddell) and Harvard (F.P.Magoun, Joseph Watmough, et many al, but especially Roman Jabobson) to the north. I was made to feel very welcome, and Bloch in particular (in Bloomfield's old chair) tried to recruit me into Bloch-Trager structuralism and teased me about Firth - though I told him he hadn't recruited me either. Now, actually, the powers-that-were at UCL 'sent' me (as they saw it) to America so that I could work lexicologically upon the great UCL Piers Plowman project that had been begun decades earlier by the then Quain Professor, R.W.Chambers.

So, after a semester at Yale, I dutifully repaired to Ann Arbor where I was generously given a desk in the great Michigan project, the Middle English Dictionary, headed by Hans Kurath and Sherman Kuhn. I enjoyed trawling through the MED's voluminous files and managed to do a few things related to my Langland mission.

I was also briefly tempted back into OE phonology to do a couple of papers with Kuhn ( Language 29.143-156 and 31.390-401). But of far greater long-term importance for me was the close contact I came to have with the stars of Ann Arbor linguistics: Charles Fries, Albert Marckwardt, Ken Pike, Herbert Penzl, Raven McDavid, for example.

I became more acquainted with the historical and contemporary relations between American and British English and (especially through seminars hospitably organised chez Fries) with modes of working empirically on the syntax of spoken language. Fries had of course already done innovative work on unedited manuscript English (soldiers' letters, for example). But now the new electronic recording had enabled him to do even more innovative work on unedited spoken English, and whatever its obvious deficiencies his book on The Structure of English (1952) gave me a huge buzz. From then on, I've never been without a tape recorder - and never above using a hidden mike. By travelling round the US, I was able to establish working friendships with many other scholars such as Jim Sledd and Archie Hill.

But I was also able to witness the darker side of academia: LSA meetings reduced to chaos, as (surely pre-planned) vilification was hurled at senior figures like Adelaide Hahn by gangs of young turks peddling their current brand of structuralism against those they saw as stuck in the mind set of the Junggrammatiker. Not a few of these same young turks were within a couple of years to desert Trager and Hill to become just as fanatical about TG, and in 1962 I was dismayed to see just such fascistic intolerance at the International Congress in Cambridge, Mass, when it was scholars like Bloch who were disgracefully shouted down. Not long after my return from the US in 1952, I moved to Durham, in no small part to get away from an increasingly bibulous departmental culture which I was not alone in finding a bit oppressive. The Durham department, headed by the critic Clifford Leech, was excellent but small, and everyone was expected to teach more or less everything. There weren't many linguists around, but there were a few very active ones such as Neville Collinge in Classics, while over in Newcastle there was my close friend, Barbara Strang. The tiny 'language side' that I was appointed to take over in Durham had been eminent in the cultural and textual history of Anglo-Saxon England, but while doing my amateurish best to keep this tradition alive I devoted myself more to convincing students and colleagues that a linguistic approach could contribute valuable insights to the study of Shakespeare, Swift, Wordsworth, Dickens, and all stations to T.S.Eliot and beyond.

And I started seriously examining the grammar of present-day and especially spoken English. That included the speech of my children.

One of them regularly (in more senses than one) spoke of 'a-r-apple', rightly divining that sandhi r was of greater phonotactic currency than sandhi n (though he didn't actually say so); and both lads contributed mightily to the series of broadcast lectures that eventually grew into The use of English (Longman). I made frequent weekend trips to London where the BBC had kindly given me not just a desk but free access to all their tapes and transcriptions of the spontaneous speech in numerous discussion programmes. I had ideas for harnessing the then vast and clumsy computer in the task of sorting out the conditions under which linguistic variants occurred, and I took a programming course with Ewan Page (later Vice-Chancellor of Reading) in his Newcastle department. The University of Durham provided modest seed money for such things as primitive recording and analysis facilities, and I was soon well on the way to devising a long-term project for the description of English syntax ('The Survey of English Usage'), described in TPS 1960, pp 40-61.

This had already received some welcome funding from a Danish publisher, from CUP, OUP, and above all from Longman by the time I moved back to UCL in 1960, bringing with me the infant Survey and a research assistant. The infant thrived and many, many people contributed to its nurture.